- PE 150

- Posts

- The U.S. Labor Market at an Inflection Point: Slowing Employment, Policy Friction, and the AI Valuation Paradox

The U.S. Labor Market at an Inflection Point: Slowing Employment, Policy Friction, and the AI Valuation Paradox

The U.S. labor market has entered a distinctly different phase of the economic cycle.

While outright deterioration remains absent, the momentum that defined the post-pandemic recovery has clearly faded. Job growth has slowed to a crawl, hiring activity has weakened across most industries, and labor demand indicators now sit at multi-year lows. At the same time, financial markets continue to advance, increasingly detached from employment fundamentals. This divergence marks a structural inflection point for both macroeconomic policy and asset valuation.

A Weak Year, Not a Collapse

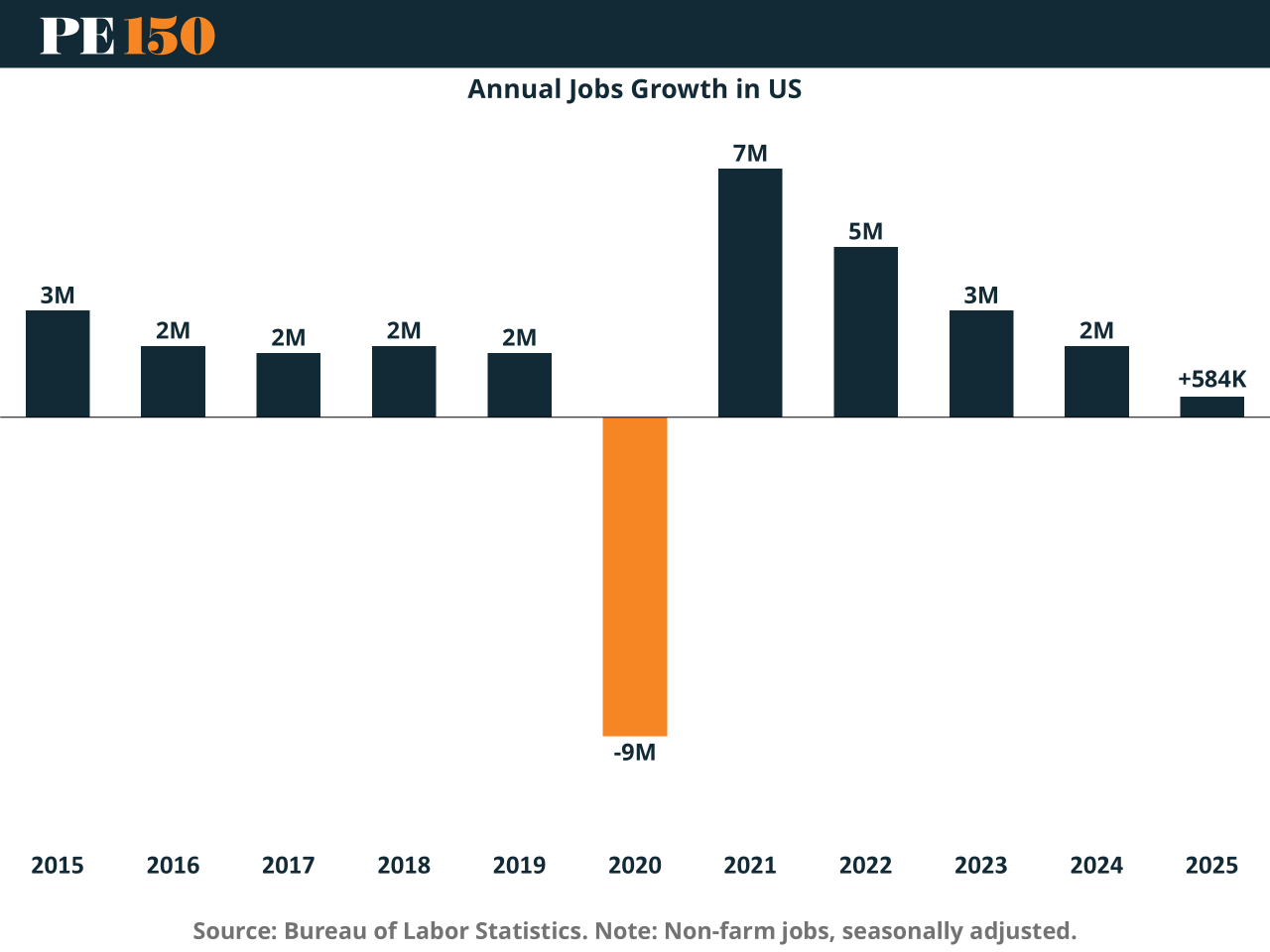

Employment growth in 2025 closed as the weakest non-pandemic year in over a decade. Net job creation totaled just over half a million positions, a sharp deceleration from the roughly two million jobs added the prior year. Monthly payroll gains remained positive but subdued, punctuated by intermittent contractions tied to government shutdown effects and policy uncertainty. Importantly, the unemployment rate stabilized rather than surged, reinforcing the notion that this is not a traditional cyclical downturn.

Instead, the labor market has settled into what can best be described as a “low-hire, low-fire” equilibrium. Employers are reluctant to expand payrolls aggressively, yet equally hesitant to initiate mass layoffs. This stasis reflects a combination of elevated interest rates, trade and tariff uncertainty, and increasing confidence that productivity gains—rather than labor expansion—will drive future output.

The annual view makes this shift unmistakable. Following the historic contraction of 2020 and the rebound of 2021–2022, employment growth has normalized sharply lower. The step down from 2024 to 2025 is particularly notable, underscoring how quickly the post-pandemic labor tailwind has dissipated.

Monthly Data Reveal Fragility Beneath the Surface

High-frequency employment data reinforces the same conclusion. Monthly job gains through late 2024 and 2025 oscillated between modest growth and outright declines. Several months recorded negative payroll prints, while positive months increasingly failed to exceed the 100,000 threshold historically associated with a healthy expansion.

The volatility of monthly changes highlights the fragility of labor momentum. Even when hiring rebounds, the scale remains insufficient to reaccelerate aggregate employment growth. This pattern is consistent with corporate behavior observed across earnings calls and surveys: firms are prioritizing margin preservation, automation, and selective hiring rather than workforce expansion.

Labor Demand Is Quietly Eroding

The clearest signal of underlying weakness lies not in payrolls, but in job openings and hiring rates. Job openings have declined steadily, reaching their lowest level in more than a year. The ratio of available jobs to unemployed workers has fallen to levels last seen in early 2021, indicating a meaningful softening in labor demand.

Hiring activity mirrors this decline. The hiring rate has slipped to roughly 3.2%, matching the lowest levels observed outside of recessionary periods. While layoffs remain historically low, voluntary quits—an indicator of worker confidence—remain muted, suggesting limited bargaining power and reduced labor market dynamism.

Sectoral data underscores the breadth of the slowdown. Healthcare, leisure, and hospitality—previous engines of job growth—have cooled. Outside of seasonal retail hiring and selective gains in construction, few industries are generating meaningful net employment gains. This is not a collapse driven by cyclical shock, but a broad-based slowdown driven by caution and structural adjustment.

Policy Uncertainty and the Cost of Capital

Monetary policy remains a central constraint. With policy rates still well above neutral, financing conditions continue to suppress labor-intensive investment. Federal Reserve officials remain divided, balancing moderating inflation against the risk of reigniting price pressures. While rate cuts remain possible, policymakers have signaled a preference for patience, particularly given lingering inflation above target.

Fiscal and trade policy uncertainty compounds the problem. Businesses remain hesitant to commit to long-term hiring amid unresolved questions around tariffs, global supply chains, and regulatory direction. This uncertainty disproportionately affects mid-sized firms, which account for a significant share of employment but lack the balance sheet flexibility of large corporations.

The result is an economy capable of generating output growth without corresponding labor growth—a configuration that challenges traditional macroeconomic models.

The Decoupling of Jobs and Markets

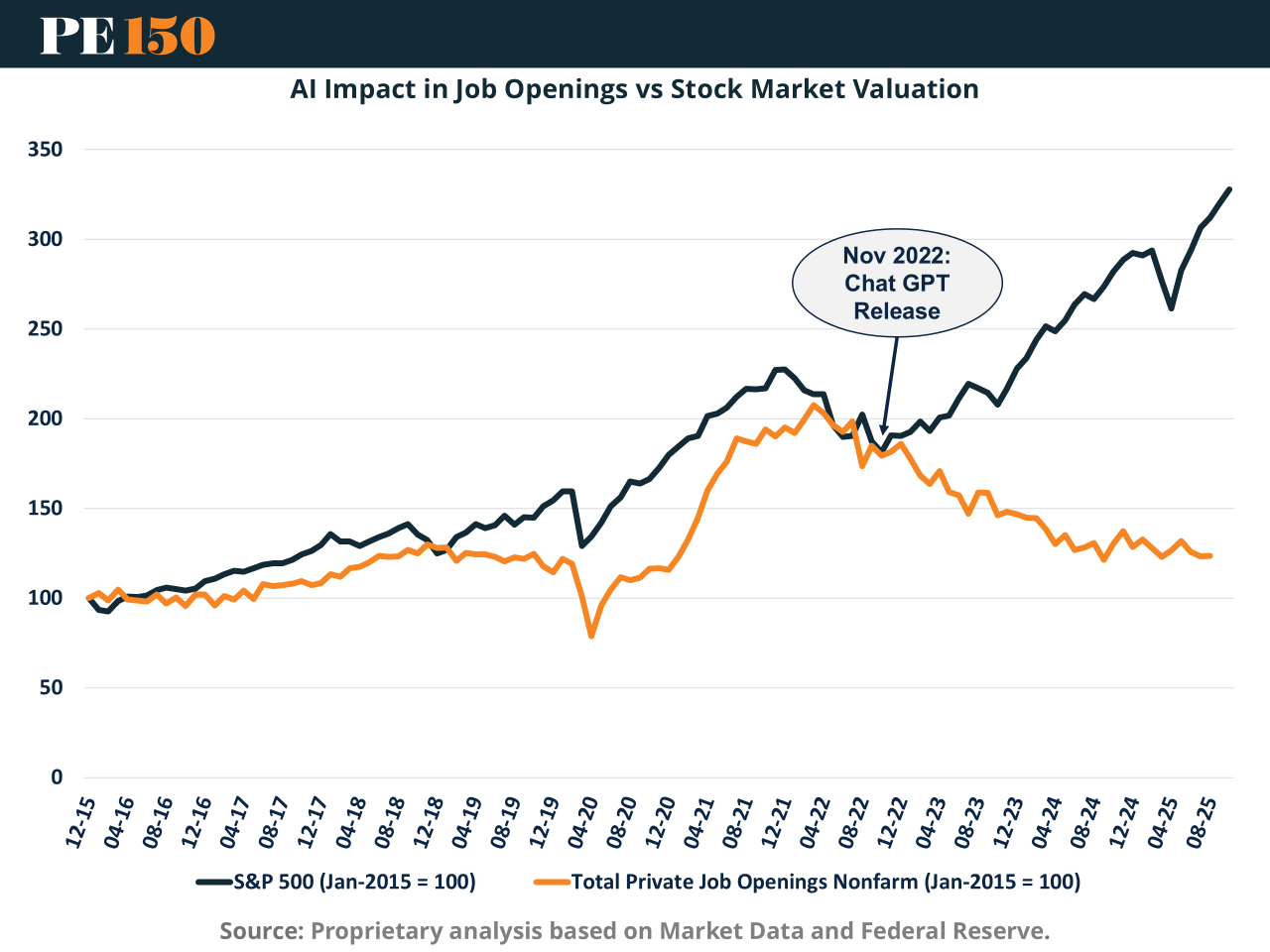

Nowhere is this shift more evident than in the relationship between employment and equity valuation. For decades, labor growth and stock market performance moved in near lockstep. Rising employment supported consumption, earnings growth, and ultimately higher valuations.

That relationship has broken.

Since late 2022, equity markets have surged even as job openings and hiring activity have trended lower. The timing is not coincidental. The release and rapid adoption of generative AI has fundamentally altered investor expectations around productivity, cost structures, and future profitability.

Markets are increasingly capitalizing anticipated efficiency gains rather than realized output growth. The assumption embedded in current valuations is that AI-driven automation will expand margins, reduce labor dependency, and sustain earnings growth even in a stagnant employment environment.

This is the defining paradox of the current cycle: valuation growth without labor growth.

The Demand Constraint Risk

While the productivity narrative is compelling, it carries an underappreciated risk. Labor income remains the primary driver of aggregate consumer demand. If employment growth continues to stagnate—or worse, declines—the capacity of households to sustain consumption comes into question.

A prolonged divergence between equity valuation and labor income risks creating a ceiling on realized profits. Firms may achieve efficiency gains, but without expanding demand, those gains cannot compound indefinitely. This tension echoes prior episodes where valuation decoupled from economic fundamentals, most notably during the late-1990s technology cycle.

Structural, Not Cyclical

The evidence increasingly suggests the labor market’s weakness is structural rather than cyclical. AI adoption, demographic constraints, immigration shifts, and policy uncertainty are reshaping labor demand in ways that traditional stimulus may not easily reverse. Even with rate cuts, firms may choose capital investment and automation over hiring.

For policymakers, this complicates the trade-off between inflation control and employment support. For investors, it raises critical questions about sustainability: how long can markets price future productivity without corresponding labor income growth?

Conclusion

The U.S. labor market is not in crisis, but it is no longer an engine of growth. Employment has entered a low-velocity regime characterized by subdued hiring, minimal layoffs, and declining labor demand. At the same time, equity markets are pricing a future defined by AI-driven productivity rather than workforce expansion.

This divergence represents a structural inflection point. Whether it resolves through renewed labor growth, weaker asset valuations, or a reconfiguration of income distribution will define the next phase of the macroeconomic cycle. What is clear is that the old relationship between jobs, growth, and markets can no longer be taken for granted.

Sources & References

CNN. (2026). The number of available jobs in the US just hit its lowest level in more than a year. https://edition.cnn.com/2026/01/07/economy/us-jolts-job-openings-layoffs-november

Reuters. (2026). US job openings slide to 14-month low; hiring weak in November. https://www.reuters.com/business/us-private-payrolls-miss-expectations-december-2026-01-07/

S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, S&P 500 [SP500], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/SP500, January 9, 2026.

The Guardian. (2026). US hiring held firm in December capping weakest year of growth since pandemic. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2026/jan/09/us-jobs-data-december-2025

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Hires: Total Nonfarm [JTSHIR], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/JTSHIR, January 9, 2026.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Job Openings: Total Nonfarm [JTSJOL], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/JTSJOL, January 9, 2026.

Wealth Stack Weekly. (2025). Tech Bust – Who Started the Ripple Effect? https://wealthstack1.com/p/tech-bust-who-started-the-ripple-effect