- PE 150

- Posts

- Maduro’s Capture and the Re-Opening of Venezuela

Maduro’s Capture and the Re-Opening of Venezuela

A Structural Shift in Global Oil and a Generational Opportunity for U.S. Private Equity

The capture of Nicolás Maduro by U.S. forces marks one of the most consequential geopolitical events in global energy markets since the Iraq War. While headlines have focused on the speed of the operation, the legal proceedings awaiting Maduro in New York, and international condemnation from adversaries such as China, the deeper implication lies elsewhere: the reactivation of Venezuela as a credible oil-producing nation after decades of socialist mismanagement.

Venezuela sits atop the largest proven oil reserves in the world—approximately 303 billion barrels, representing nearly 20% of global reserves, according to OPEC. As shown in the chart above, Venezuela alone surpasses Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq, and the United Arab Emirates. Yet despite this geological endowment, the country contributes only 1.3% of global oil production, a staggering mismatch between potential and reality.

This gap is not a function of resource scarcity or technical infeasibility. It is the direct outcome of corruption, underinvestment, sanctions, nationalization, and the hollowing out of PDVSA under socialist rule. With Maduro removed and the possibility of a long-term political realignment emerging, Venezuela now represents not merely a geopolitical story—but a multi-decade capital deployment opportunity, particularly for U.S. private equity.

Oil Markets React: Signal, Not Noise

Immediately following the U.S. operation, oil prices moved higher. Both Brent and WTI crude posted gains, reflecting heightened geopolitical risk and the market’s reassessment of supply optionality. However, as shown in the previous chart, these moves were modest in historical context. Prices remain well below the peaks seen during the 2022 energy shock and far from pricing in a material Venezuelan production surge.

This market behavior is critical. It suggests traders understand that Venezuela is not a short-term supply solution. Decades of decay cannot be reversed in 12 or even 24 months. Infrastructure is degraded, fields are damaged, pipelines are corroded, refineries are dysfunctional, and skilled human capital has fled the country.

In other words, oil markets are reacting rationally. The capture of Maduro removes a political barrier, but it does not instantly unlock barrels. That distinction is precisely what creates asymmetric opportunity for long-duration capital rather than short-cycle oil traders.

Venezuela’s Collapse Was Political, Not Geological

At its peak in the late 1990s, Venezuela produced approximately 2.5 million barrels per day. Today, output fluctuates around 1.1 million barrels per day, and even that figure is widely considered fragile and unsustainable without continuous stopgap measures.

Rystad Energy estimates that $53 billion over 15 years would be required merely to keep production flat at current depressed levels. Restoring output to pre-Chávez levels—and eventually beyond—would require far more capital, deployed patiently and insulated from political whiplash.

This is where the traditional oil majors hesitate. Exxon Mobil and ConocoPhillips still carry institutional scars from forced nationalizations in the 2000s. Chevron, the only major U.S. operator still present, has signaled caution rather than expansion. Public oil companies are structurally ill-suited to bear sovereign transition risk under quarterly earnings scrutiny.

Private equity, by contrast, is structurally designed for exactly this environment.

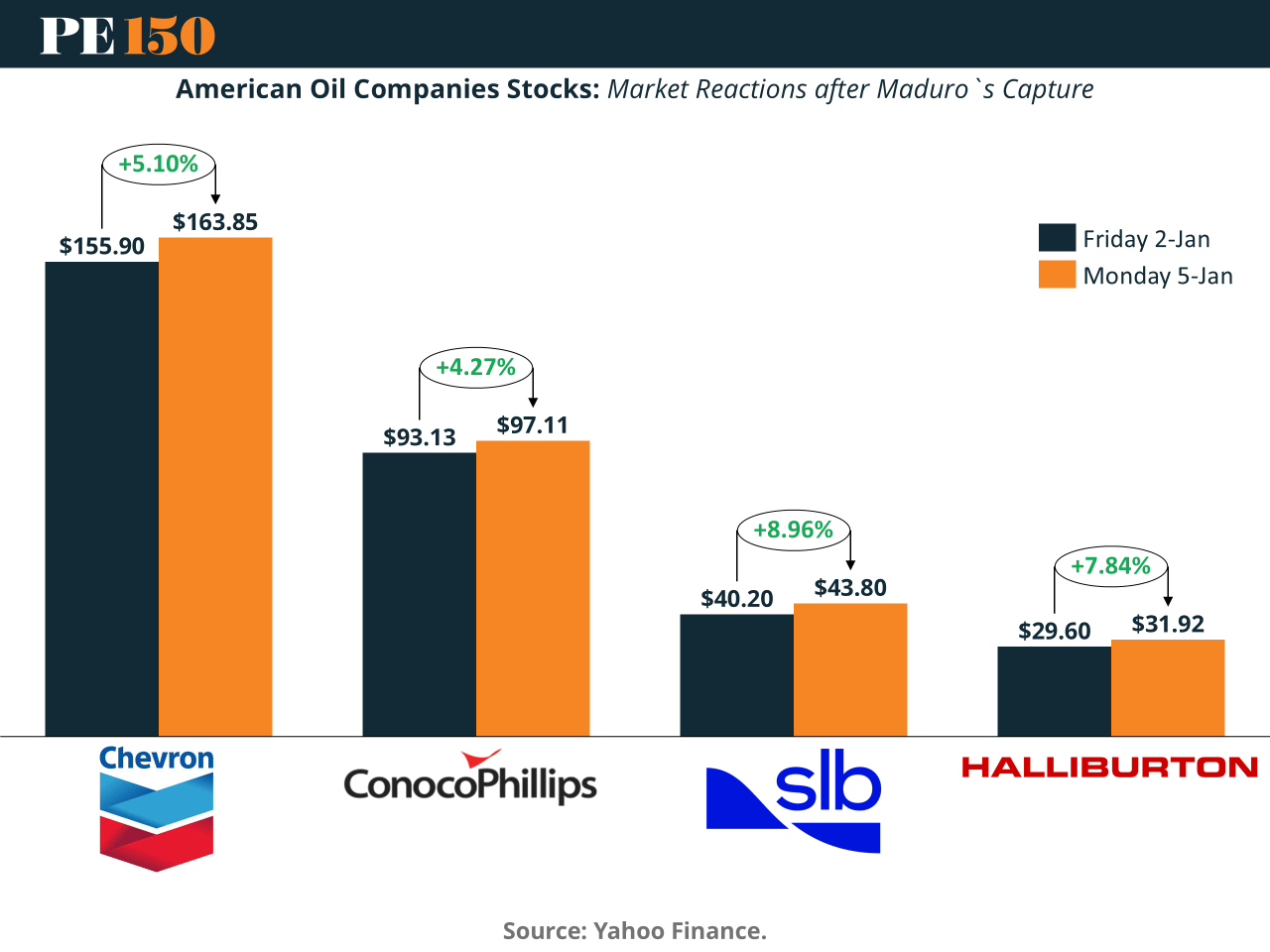

Equity Markets Reacts

Equity markets immediately priced in the option value of Venezuela. As shown in the previous, Chevron rose more than 5%, ConocoPhillips gained over 4%, while oil-services firms like SLB and Halliburton posted even larger percentage increases.

These moves were not driven by near-term earnings upgrades. They reflect investor recognition that a regime change could unlock decades of upstream, midstream, and services demand. Importantly, oil-services firms—whose revenues depend on sustained capital expenditure—outperformed, reinforcing the idea that markets are thinking of long cycle, not short spike.

However, public equities can only capture part of this upside. The real transformation—pipelines, export terminals, refineries, power generation, water treatment, logistics—will occur off public balance sheets, financed by private capital.

The Demographic and Political Reset

Venezuela’s collapse produced one of the largest migrations in modern history. More than 8 million Venezuelans fled the country, hollowing out its workforce and middle class. This diaspora is overwhelmingly anti-socialist, economically pragmatic, and capital-aware.

If a post-Maduro political settlement stabilizes—particularly one anchored in property rights, dollarization, and foreign investment protections—the return of even a fraction of this population would represent a powerful economic catalyst. Skilled engineers, operators, financiers, and entrepreneurs would return with human capital and international networks intact.

Critically, the political lesson is likely permanent. After two decades of deprivation, Venezuelan society is unlikely to vote again for radical leftist economic models. This implies not a temporary policy shift, but a generational turn toward market-oriented governance—exactly the condition long-term investors require.

Why Private Equity, Not Oil Majors, Will Lead

As shown in the chart above, oil prices remain volatile but structurally supported. Even in a world of energy transition, oil remains indispensable. Incremental supply growth increasingly comes from complex, capital-intensive projects rather than easy barrels.

Venezuela’s heavy crude fits this reality. Development requires:

Massive upfront capital

Long payback periods

Integrated infrastructure investment

Political risk underwriting

Operational restructuring

These are precisely the domains where U.S. private equity excels. Infrastructure funds, energy funds, and hybrid Private Credit vehicles can structure investments and/or provide cash with downside protection, sovereign guarantees, offtake agreements, and layered capital stacks.

Unlike oil majors, PE funds can:

Accept illiquidity

Price political risk explicitly

Control assets directly

Partner with multilaterals (IFC, World Bank, IDB)

Exit opportunistically via IPOs or strategic sales once risk compresses

A Blueprint for Rebuilding Venezuela’s Oil Complex

A credible investment roadmap would unfold in phases:

Phase 1: Stabilization

Emergency repairs to pipelines and refineries

Power and water infrastructure restoration

Governance reset at PDVSA

Production stabilization at ~1.2–1.4 mbpd

Phase 2: Expansion

Field redevelopment and enhanced recovery

New export terminals

Heavy crude upgrading capacity

Output growth toward 2.0–2.5 mbpd

Phase 3: Integration

LNG, petrochemicals, refining

Regional energy hubs

Public listings of restructured assets

Gradual re-entry of oil majors at higher valuations

At every stage, private equity could sit at the center—not as a short term speculative player, but as the system architect for the long run.

Conclusion: A Once-in-a-Generation Energy Reset

Maduro’s capture does not guarantee Venezuela’s recovery. But it removes the single largest obstacle to rational economic reconstruction. The world’s largest oil reserves have been offline not because of geology, but ideology.

For oil markets, this represents a long-term supply optionality that caps extreme price upside without depressing prices in the near term. For U.S. geopolitics, it reasserts influence in the Western Hemisphere. And for private equity, it presents a rare opportunity to deploy patient capital at the intersection of energy and infrastructure.

If Venezuela does turn decisively to the right—politically, economically, and institutionally—the next decade may witness the largest energy reconstruction effort of the 21st century. Those who understand that this is not a trade, but a structural investment, will define the next chapter of global oil.

Sources & References

Barron`s. (2026). Trump’s Venezuela Action Is Boosting Oil Stocks. Why the Raid Was the Easy Part. https://www.barrons.com/articles/trump-venezuela-oil-stocks-things-to-know-today-36895ab4?siteid=yhoof2

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Spot Crude Oil Price: West Texas Intermediate (WTI) [WTISPLC], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/WTISPLC, January 6, 2026.

OPEC. (2025). 2025 Annual Statistical Bulletin. https://www.opec.org/assets/assetdb/asb-2025.pdf

Statista. (2026). Venezuela Sits on a Fifth of the World's Oil. https://www.statista.com/chart/16830/countries-with-the-largest-proven-crude-oil-reserves/

U.S. Energy Information Administration, Crude Oil Prices: Brent - Europe [DCOILBRENTEU], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DCOILBRENTEU, January 6, 2026.

Yahoo Finance. (2026). Venezuela oil: Energy giants likely to invest in infrastructure. https://finance.yahoo.com/video/venezuela-oil-energy-giants-likely-163000705.html

Yahoo Finance. (2026). US invades Venezuela, market reaction, CES kicks off: 3 Things. https://finance.yahoo.com/video/us-invades-venezuela-market-reaction-140801122.html